At Sea: In the North Atlantic Day 15

The Chief Scientist is standing on the bridge, looking out over the sea and grinning as if all his Christmases have come at once. The Bosun is scowling at the radar and muttering about this taking a year off the life of the ship. The wind speed display says 65 knots, maximum measurement today 90 knots. Today is the day we came out here for.

We want to understand how gases and tiny particles come in and out of the ocean when the wind speed is very high. The Earth is a giant connected system, and if we want to understand our weather, and how both the atmosphere and the ocean behave, we need to track those connections. Gases like carbon dioxide go into the ocean in some places and come out in others. This happens all the time, but it’s a very slow process when there’s no wind. As the wind speed increases, the ocean breathes more deeply. We often plot the amount of gas exchange with wind speed, and it starts off fairly flat and then as the wind speeds increase, the exchanges get huge. Big storms with very high winds are disproportionately important, but we don’t know by how much. At the moment, those plots showing gas flux with wind speed go from a wind speed of 0 metres per second up to about 17 metres per second (about 38 mph). Then the plots stop.

This morning, when I woke up, the wind was blowing at 60 knots, 30 metres per second, 67 mph. The data we get today will be plotted in new territory, and will let us see the direct effect of these big storms for the first time. That’s why the Chief Scientist is grinning like a Cheshire Cat. He’s been looking forward to this storm ever since it first appeared on the forecasts. And it’s turned out to be even bigger than the forecasts suggested.

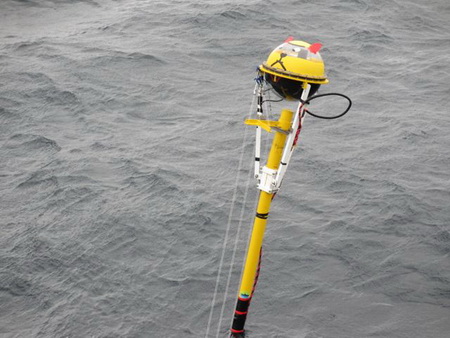

We put the big yellow buoy out yesterday, after three days of relative calm. It’s now got a face on it (two weeks at sea and already it’s silly season), and there’s a list of potential names for it on the whiteboard in the lab. Twitter and facebook are joining the game, and the most common suggestion by far is “Bob”.

The big buoy looked like such a monster when I first saw it on the dockside in Southampton. But out here, it looks fragile. I’ve set everything on it to record intensively for 36 hours, as we pass through the eye of the storm and back out again. I’m not even sure what the data will look like – there are so many bubbles out here that the sea surface has gone white. I’m just hoping that it survives mostly intact.

It’s a quiet day on board. The ship is bouncing and swaying, and it’s impossible to concentrate on desk-based work. Most people are napping, or up on the bridge watching the spectacle. And the spectacle is just awesome. I love it! I could spend hours up there. The swell has built and it’s now around 12-14 metres, and we’re facing right into it. As these vast rolls of water come towards us, the bow dips into it and then rides right back up, occasionally crashing through the waves if it can’t change direction in time. The surface is covered in trails of bubbles being blown by the wind, and you can see the bubble plumes left by previous huge breakers sitting under the surface. It’s as if the surface of the ocean is being blown away, snatched from the top and the sides of a mountainous waterscape that never stops moving.

We should be through the worst of it by midnight tonight, and then it will take a couple of days for the wind and waves to die down enough to get the bubble buoy back out and retrieve the data. I’ll only relax properly when I’ve seen the data back on board – there’s always the risk that something didn’t switch on or that a watertight case leaked.

But for the time being, I’m going back up to the bridge to watch. Out here, today, there are more bubbles than I’ve ever seen in my life at one time. Never mind that trip to the Champagne region, looking at champagne bubbles. This, out here in the middle of the north Atlantic in a storm, this is the bubble physicist’s dream day out.